Operations | Process | Resources | Strategy

STAY CONNECTED AND SIGNUP TO RECEIVE INSIGHT updates

Think of a production system and you’ll probably conjure up some kind of assembly line. Whether you imagine humans or machines doing the work, this mental model feels wedded to manufacturing. It needn’t be—production principles are universal.

An airline’s check-in desk is part of a production line. So is the hospital’s procedure for admitting patients. Running scripts in software development is production. As is the sales pipeline that gets software to market. Insurance claims and loan applications? Production systems. And the barista in the café offers a vivid everyday production system—so obvious we almost don’t see it as such.

Perhaps we don’t naturally think of these examples as production environments because they don’t result in physical products that would hurt if you dropped it on your toe. But even the kind of heavy industrial environments we at Ensemble operate in offer plenty of counterintuitive examples, including:

- managing technical service requests in an engineering environment

- processing contractor applications for mobilisation to site

- onboarding employees into vacant project positions

- processing accounts payable and receivable

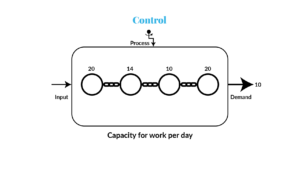

All these examples are production systems that benefit from a systemic approach. Let’s examine a simple process made up of four steps, each of which is linked to the other. And let’s say the capacity to do work for each step is as shown in the diagram. It doesn’t really matter what the process is, but let’s use technical notifications as an example.

Let’s say that the person at the first work-centre, an inspector, generates 20 notifications per day. The person at the second work-centre has the capacity to assess 14 of those notifications per day. The highly skilled planner can only manage to plan 10 notifications per day and, at the end of the process, back office has capacity to close out 20 notifications per day.

On the demand side, the manager of the process has been told to allow for a regular demand of 10 notifications per day. In the majority of cases, the manager would be looking very closely at costs and would wonder:

Why do I have all this extra capacity? The planner can only handle 10 units per day, so she’s the bottleneck. Yet this capacity perfectly meets demand.

So I’ll scale back the capacity of all the work-centres to 10. This will balance the system to match the demand while reducing costs by removing unneeded extra capacity.

The manager who thinks this way, trying to perfectly balance supply and demand across a connected sequence of steps is in for a nasty surprise. With the newly ‘balanced system’ (all work-centres at 10 capacity), production consistently falls short. Why? The manager discovers that common cause variation means that each of the steps in the process has only a 90% chance of processing their full quota of 10 notifications per day.

By the laws of statistics, the cumulative probability of getting ten completed is reduced to 90% to the power of 4—that is, 90% x 90% x90% x90%—or a cumulative 65%. In other words, almost one in three notifications would not be completed on time. The name of this statistical fact is covariance—when there are individual fluctuations between dependent events.

And of course, over in the real world of the plant, what if equipment failure increases and demand changes? If it’s lower than forecast, we end up with people standing round idle. While if it’s higher than forecast, we delay return to service.

First, find your constraint

If, as per the Theory of Constraints, systems are governed by their constraints, the first thing we must do, is to find the constraint. What’s yours? Do you know? Is it where it is because you’ve designed your value-creation engine to take advantage of the laws of physics? Or are you forever its victim, watching it turn up, unannounced, in a different place every day…like whack-a-mole?

Once we find our constraint, if we want to optimise its performance for value creation. How can we go about doing that?

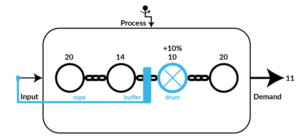

The TOC approach to managing production systems is called Drum Buffer Rope (DBR). Let’s take a closer look at how Dr Eli Goldratt, the physicist founder of the method came up with such a name.

The constraint in our example is the planner, who can only plan 10 jobs per day. We call this bottleneck resource the drum, because it beats the rhythm of value creation. The power of the solution lies in the fact that a 10% gain at the drum is a 10% gain for the system as a whole. That is, 10% more capacity for the planner means 10% more production for the whole maintenance system. 10% more production for the maintenance system means less downtime, more reliable performance and more throughput. By the same logic, increasing the capacity of a non-constraint by 10% has no positive effect on the system and, in fact, may produce a negative effect by increasing the backlog and stress at the bottleneck.

“A 10% gain at the drum is a 10%

gain for the system as a whole”

In most cases, the value of that gain in throughput dwarfs whatever gain there might be in micromanaging the operating expense of each component part. Moreover, designing your production around your drum lets you use it as a synchronisation tool for the whole—everyone marches to the same drum beat. And, it bears repeating, because by definition everyone has more capacity than the drum, 10% gained at the drum is 10% gained for the system as a whole.

Understanding this requires a mindset shift. Everyone has to play as one band. If the drum is starved because the upstream process was goofing off or produced the wrong component, the whole system loses out. So how do we ensure that the drum never runs out of work? Well, we place a buffer in front of it. This buffer is in effect the stored capacity of the upstream functions. We want to size the buffer so that it’s not so big as to flood the engine with work in progress, but not so small that the drum misses a beat because it’s starved. This is why everyone on the team has to understand the idea of supporting the constraint—their colleagues working at the drum.

To keep the size of the buffer right, we tie a rope to the release of inputs at the entry point to our engine. The buffer is sized to be big enough to accommodate the time it takes from the input step until it is ready to be processed by the drum. As soon as the drum has begun work on the buffer, it gives a tug on the rope to release the next work packet, such that it arrives in good time to keep the whole value-creation engine running smoothly.

And, yes, the rope means that occasionally those working in non-constrained work-centres will be asked to slow down, or even stop work, so as not to flood the engine. This is profoundly counter-intuitive to our natural assumption of what it means to be ‘productive’.

With our drum-buffer-rope system in place, we give our system its best chance of 10 out of 10 performance. At this point, there is no way to squeeze more juice out of the system in its current configuration. If we want to uplift the system now, we need to invest in additional resources. Most organisations jump straight to this step long before they need to—and often with unintended consequences.

Adding another planner at the drum takes the combined uplifted capacity to 20 jobs, which is at first glance more than the plant demands. The internal constraint of the production system has become external. It’s time to find new tasks to which we can put this hitherto hidden capacity. Could we encourage the team to be more proactive in bringing innovation to their work? How might they use the time dividend released to contribute to ensuring that ever shorter turn-times deliver ever more throughput—reliably, on time and at the requisite quality?

Let’s recap the steps to implementing DBR—one of the twentieth century’s least known, but most effective, innovations in productivity:

- Establish your process flow

- Quantify the capacity available at each process step based on the demand for each unit of production

- Find which process step represents the bottleneck to overall process productivity and declare it the ‘drum’

- Establish how long it takes for work to flow from the start of the process to the drum, then create a ‘buffer’ that keeps the drum fed for at least that lead-time

- Develop a mechanism to signal release of the inputs by tying a ‘rope’ from the drum to input release

- Monitor when the drum is running at or near systemic capacity (say 80% of maximum nameplate) and prepare to uplift system capacity and reassign the drum

One final note. It is a tragic truth that most managerial leaders are all too keen to use the productivity gain of DBR to fire people who they believe are now surplus to their requirements. This mindset completely misunderstands the ‘systems thinking’ approach to improving production. Firing people may provide a short-term cost-saving, but is foolish in the medium- and long-term if you want to develop a culture of continuous improvement which, after all, is the only way you can sustainably compete. Why would employees wish to improve production if they knew that in doing so, they would be putting their own jobs at risk?

To accomplish the principles of Just Work—in which everyone has the right to be well-managed—we must rather tap into aspiration and imagination. Do the hard yards of gaining the trust of your workforce to co-create better ways to do better work.

____________________________

The Theory of Constraints offers a new operating system fit for our complex world of change. To learn what that operating system might look like, we invite you to download our Executive Guide to Critical Chain Project Management [PDF].

The change of mindset from standard thinking to Theory of Constraints (TOC) is both profound and exhilarating. To make it both fun and memorable, we use a business simulation. Just as astronauts need a few zero-gravity rides in a special aircraft before they experience the real thing in space, the game simulates the effects of TOC. We call it The Right Stuff workshop and we’d love to run it with you.

____________________________

[Background photo: ‘Coffee smarts’ by Nathan Dumlao on Unsplash]

[Background photo: ‘Coffee smarts’ by Nathan Dumlao on Unsplash]

“Every situation, no matter how complex

it initially looks, is exceedingly simple”

—Eliyahu Goldratt

Measurably reliable and agile

Few performance standards deliver the competitive advantage you gain by keeping your promise to deliver on time, doing so faster than your competitors, and suffering no defects while you’re about it.(more…)

Managing accounting’s relevance

Eli Goldratt famously said, ‘Tell me how you measure me, and I will tell you how I will behave. If you measure me in an illogical way… do not complain about illogical behaviour.’ If you measure and reward activity, then activity’s what you’ll get.(more…)

More than just work

Discover better ways to do better work.

Fresh insights, every Friday

We alternate our own actionable articles with three relevant links from other authorities.

We’ll only use your email address for this newsletter. No sales callsMore than just work

Discover better ways to do better work.

Fresh insights, every Friday

We alternate our own actionable articles with three relevant links from other authorities.

We’ll only use your email address for this newsletter. No sales calls

What is to get in touch with you?